A new kind of technology is entering public consciousness, and it has some truly unique properties. It’s perhaps the first major technological revolution that won’t require a hardware change.

Its power will be felt through old devices. It’ll change phone calls as much as it will software programming. It will reach us by screen and through mail, in information queries and customer service complaints.

Its infrastructure is already laid.

Lex Fridman asked Jeff Bezos what he thought of generative AI, the large language models behind booming platforms like ChatGPT, Dall-E, Grok, and soon, many others.

Bezos: “The telescope was an invention. But looking through it at Jupiter, knowing it had moons, was a discovery. Large language models are much more like discoveries. We’re constantly getting surprised by their capabilities.”

It’s a fascinating assertion, and it’s a unique explanation for this problem. Why are we surprised by a technology we created?

Bezos: “It’s not an engineered object.”

According to doomsayer technopriests and at least one former Google engineer, this is a step on the path to a new kind of consciousness—”general AI.” But when asked if his platform was conscious, or close to it, the founder of ChatGPT Sam Altman said, “No, I don’t think so.”

Bezos: “We do know that humans are doing something different in part because we’re so power efficient. The human brain does remarkable things and it does it on about 20 watts of power… The AI techniques we use today use many kilowatts of power to do equivalent tasks.”

He uses the example of driving to illustrate the point. To learn the rules of the road, self-driving cars require billions of miles of driving experience. An average 16-year-old learns to drive in about 50 hours.

Despite generative AI’s incredible feats of passing both the Bar exam and the US Medical Licensing exam, this technology seems to learn and think very differently than the fat computers in our skulls do.

It also tends to lie.

A Duke University researcher found that ChatGPT would fabricate sources that sound scholarly but aren’t real, which started a cascade of follow-on pieces about why ChatGPT “lies.”

But to say that ChatGPT “lies” is to put conscious agency on an unconscious algorithm. We use the metaphor of consciousness to describe our interactions with generative AI because it’s useful shorthand, but there’s an important distinction to be made here.

In his conversation with Bezos, Fridman observes, “It seems large language models are very good at sounding like they’re saying a true thing, but they don’t require or often have a grounding in a mathematical truth. Basically, it’s a very good bullshitter.”

Bezos responds, “They need to be taught to say, ‘I don’t know,’ more often.”

What we’re discovering through the telescope of generative AI isn’t a new kind of consciousness. First and foremost, we’re discovering the immense power bound up in the huge amount of information we’ve amassed in the building of the Internet.

What we’re discovering through the advent of large language models is that simply by scaling up the available information, technology is able to produce astounding results.

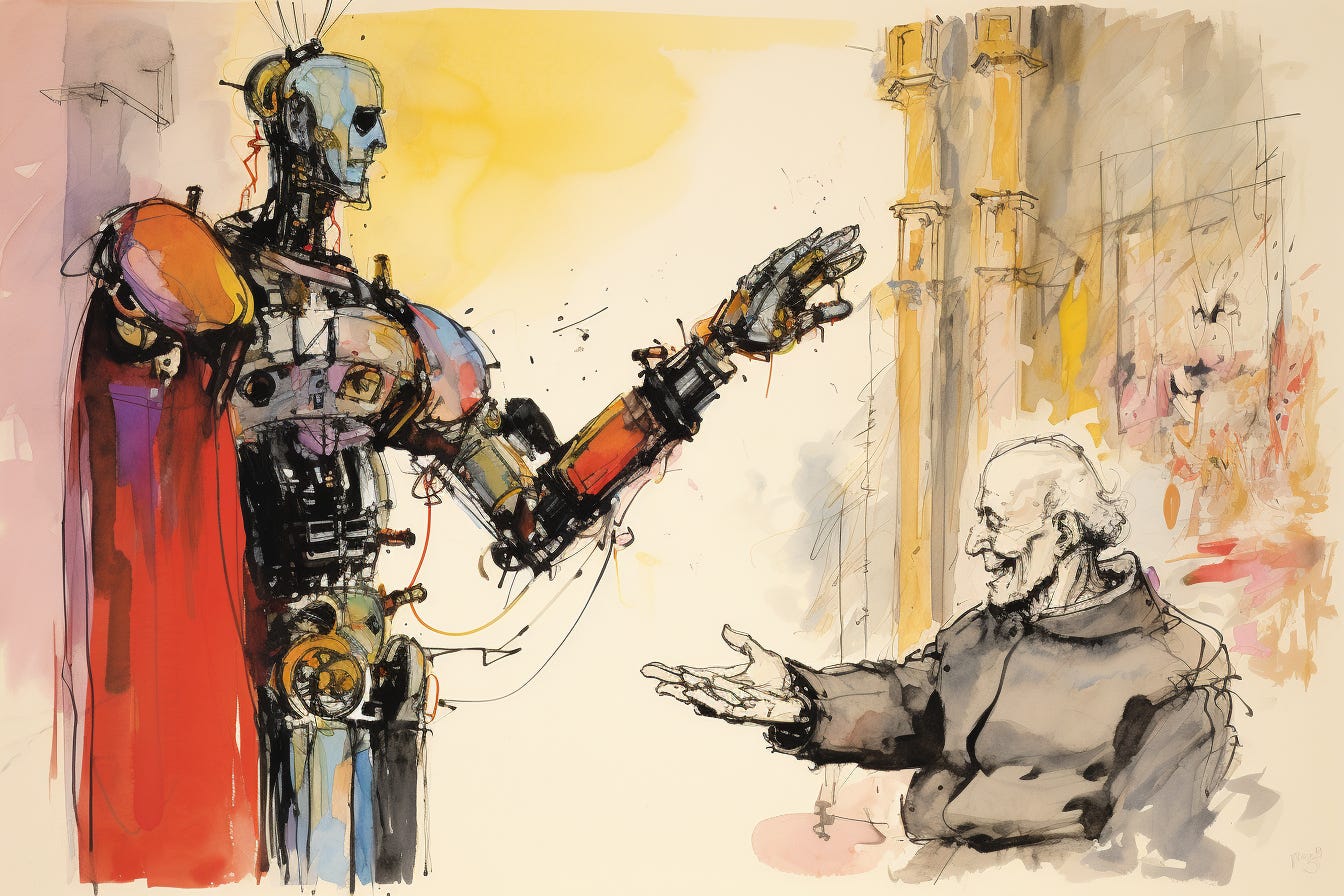

The creativity that many hoped would be the final bastion of human competence seems not to be in the brush of the painter or the keystrokes of the writer. If you’ve enjoyed the images in this article so far, they were created with Midjourney by prompting Quentin Blake-inspired illustrations.

Rather, what we’re finding is that as we create more and more complex tools, it’s our unique ability to find applications and leverage points for those tools that separate human consciousness.

It’s our ability to discern signal in an infinitely noisy universe.

When Dall-E fails to capture the subtle anatomy of a hand, it’s immediately obvious to our eye. Something feels off.

A subtle mistake made by an exceedingly-convincing, authoritative-sounding tool with a 99% accuracy rate and access to nearly every piece of available data is detected by a 20-watt brain that’s powered by ham sandwiches.

Even the simple process of developing AI illustrations is one of discerning signal among noise. There’s a natural feedback process in the use of a language-to-image tool, and we don’t really need to learn it. We input a prompt, we get a result, and we adjust our prompt.

We’re discerning where there is meaning—or something close to it. We’re adjusting the framework by offering new prompts. And we discern from the things created which are worth keeping.

As new generations of tools are placed in our hands, it’s our role as curators and strategists that will persist. While there are some strong emotions around technology with the potential to displace creative jobs, these tools are so immediately useful that only forcible intervention will slow them down. It’s hard to stop humans from building on the work of the past.

In a Discord conversation with the Midjourney community, its creator David Holz said that he wanted the tool to “be like a paintbrush. I want everyone to have it.”

If Michelangelo created the Sistine Chapel with paintbrushes, what will we create with generative AI?