This post is the encapsulation of my thoughts on AGI evolution, which I’ve variously written about eg here and here. Feel free to just check out the equation and skip to the last section if you’d rather cut to the chase and start the debate.

There is a persistent worry amongst smart folks about the creation of smart and capable artificial intelligences, or AGI. The worry is that by its very nature it would have a very different set of moral codes (things it should or shouldn’t do) and a vastly increased set of capabilities, which can result in pretty catastrophic outcomes. Like a baby with a bazooka, but worse. Metaculus now predicts weak AGI by 2027 & strong AGI with robotic capabilities by 2038.

To put my bias upfront, I’ve not found this to be very persuasive. From an epistemological point of view, “it can be dangerous” seems like insufficient grounds to worry, and “we should make it safer” seems like a non sequitur. Like sure, make it safer, but since nobody knows how it feels like a lot of folks talking back and forth with each other. We wouldn’t have been able to solve the horrors of social media before social media. We couldn’t have solved online safety before the internet usage soared and costs plummeted. Jason Crawford has written about a philosophy of safety and how its part of progress and not separate from it.

However as every new instance of AI enabled tech dropped, both camps of accelerationists and doomsdayers say the same things. Imagine if this continues to get powerful at the same rate. Imagine if this technology falls into the wrong hands. Imagine if the AI we created doesn’t do what we tell it to do, through incompetence or uncaringness or educated malice.

The core of the worry segment lay in the idea that capabilities do not rise at the same rate as the knowledge to wield the capability wisely. The best examples are this paper from Joe Carlsmith, and this research article from Ajeya Cotra. I’m not gonna try to summarise them, because they’re extremely information dense and assumption laden, but the conclusion includes two components – that as intelligence and ability within the machine increases we lose our ability to control it, and that it might not value the things we value, thus causing inadvertent chaos.

This feels very much like creating an anthropology for a species that doesn’t exist yet.

While I’ve written about the idea of AI doom as eschatology before, and am very much in the techno-optimist camp about its potential, when multiple smart people are freaking out about the same problem its useful to check if its people being nerd-sniped.

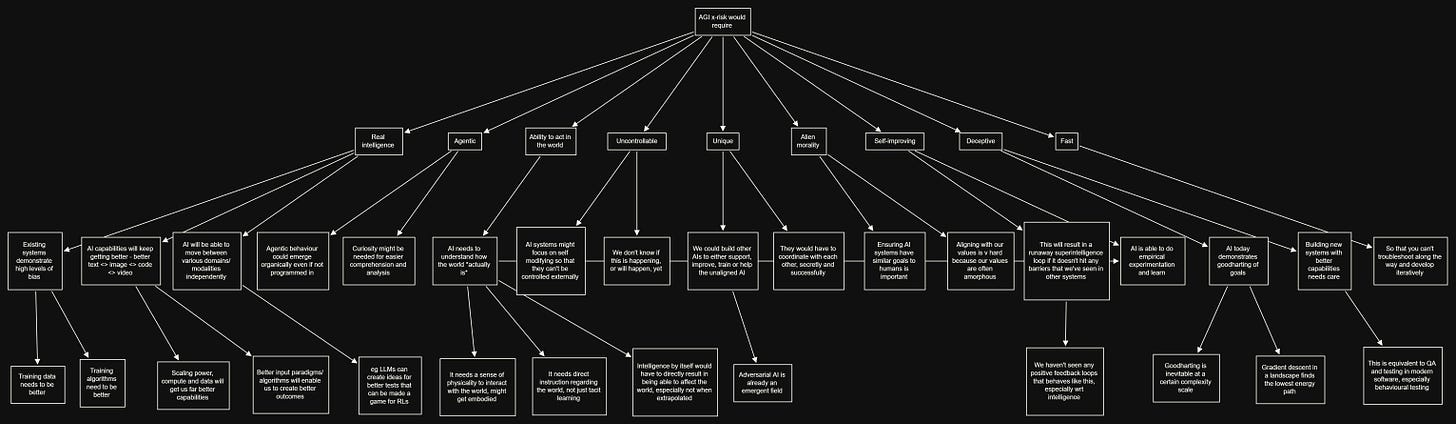

The first problem is how to break the problem down. Because ultimately a lot of the ways in which AI makes everyone grey goo, or sets off all nuclear bombs, or creates a pathogen, assume a level of sophistication that basically begs the answer. So I looked at where we’ve grappled with the ineffable before, and tried to somehow break down our uncertainty about the existence of a thing, in this case a malevolent entity that an uncomfortably large percentage of the population are happy to call a demon.

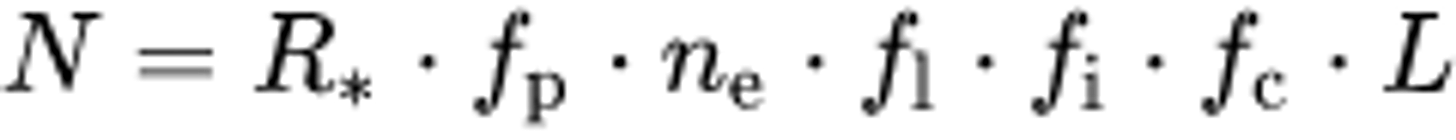

We’ve looked at calculating the incalculable before. Most famously, in 1961, the astrophysicist Frank Drake asked how many extra-terrestrial civilisations there could be. To answer this, he created his eponymous equation.

You can think of this as a first principles Fermi estimation. Based on your assumptions about the things it takes to create an alien lifeform, the rate of star formation, fraction of those with planets, fraction which can support life and actually develop it, fraction of those with civilisations which will eventually become visible to us. As Frank Drake actually said:

As I planned the meeting, I realized a few day[s] ahead of time we needed an agenda. And so I wrote down all the things you needed to know to predict how hard it’s going to be to detect extraterrestrial life. And looking at them it became pretty evident that if you multiplied all these together, you got a number, N, which is the number of detectable civilizations in our galaxy.

Each one of those fractions are of course highly variable, but the idea is to get a sense of the inputs into the equations and help us think better. Or in the words of the new master.

The Drake equation is a specific equation used to estimate the number of intelligent extraterrestrial civilizations in our galaxy. While there may be other equations that are used to estimate the likelihood or probability of certain events, I am not aware of any that are directly comparable to the Drake equation. It is worth noting that the Drake equation is not a scientific equation in the traditional sense, but rather a way to help organize and structure our thinking about the probability of the existence of extraterrestrial life.

The Drake equation is a way to distil our thinking about extremely complex scenarios around the emergence of alien life, and in that vein it’s been really helpful.

Which made me think, shouldn’t we have something similar regarding the emergence of artificial alien intelligence too? I looked around and didn’t find anything comparable. So, I decided to make an equation for AGI, to help us think about the worry regarding existential risk (x-risk) from it’s development.

Scary AI = I * A1 * A2 * U1 * U2 * A3 * S * D * F

(Since publishing I found

created his own version of the equation a couple months ago here. It’s similar enough that I feel confident we’re both not totally wrong, and different enough that you should read both. Jon’s awesome anyway so you ought to read him regardless.)

Let’s take a look.

% probability of real Intelligence

Hard to define, but perhaps like pornogrpahy easy to recognise when we see it. Despite the Deutschian anguish at behaviourism, or rather the referred Popperian anger, it’s possible to at least see how a system might behave as if it has real intelligence.

There are ways to get there from here. When I wrote about the anything to anything machine, which AI is developing, part of the promise needed was to make it seamlessly link with each other, so each model is not sitting in its own island.

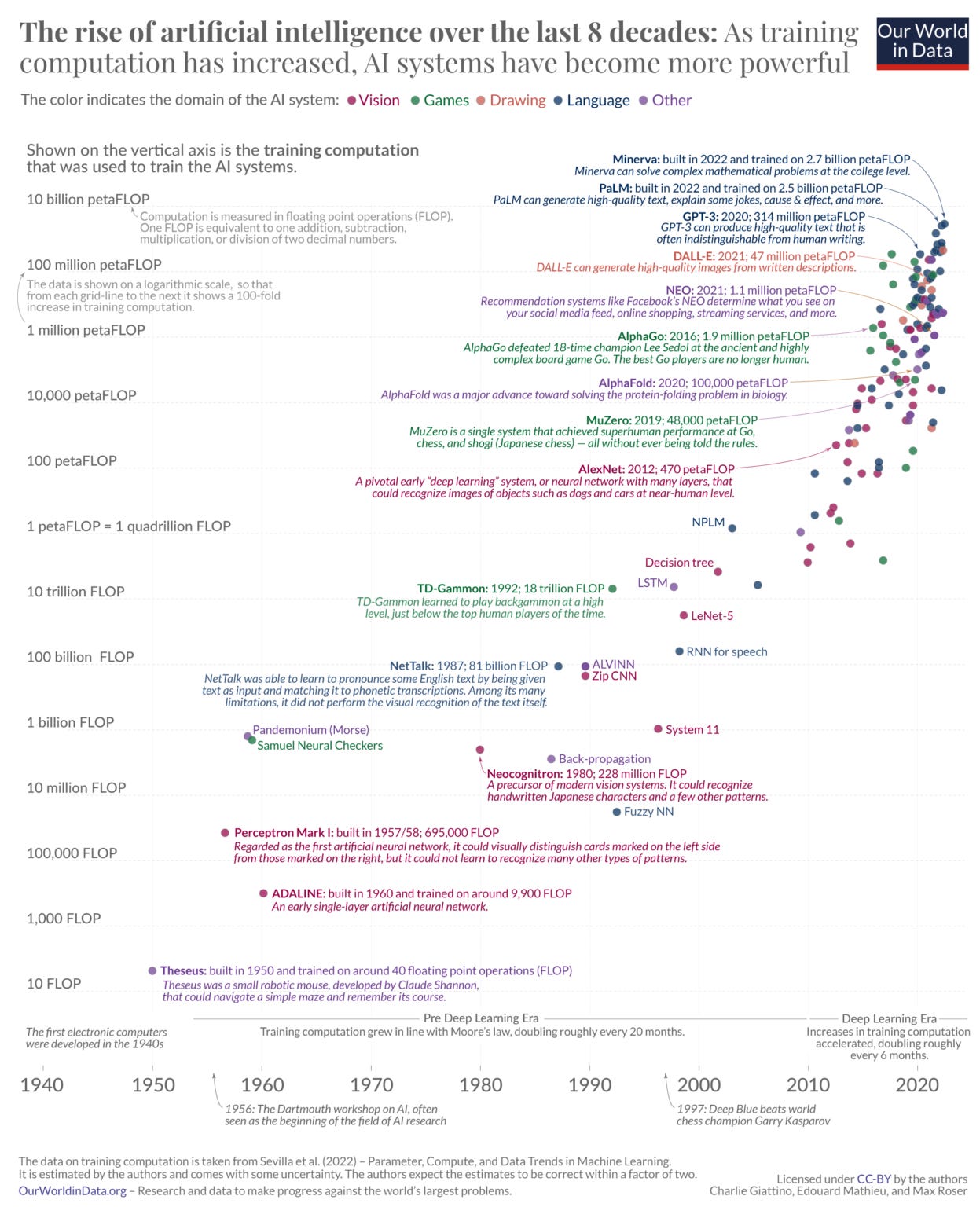

You need far better, or far more, training data. We actually don’t know how much is needed or at what fidelity, since the only source of real intelligence we’ve seen is the result of a massively parallel optimisation problem over a million generations in a changing landscape. That’s distilled knowledge and we don’t actually know what’s really needed to replicate that.

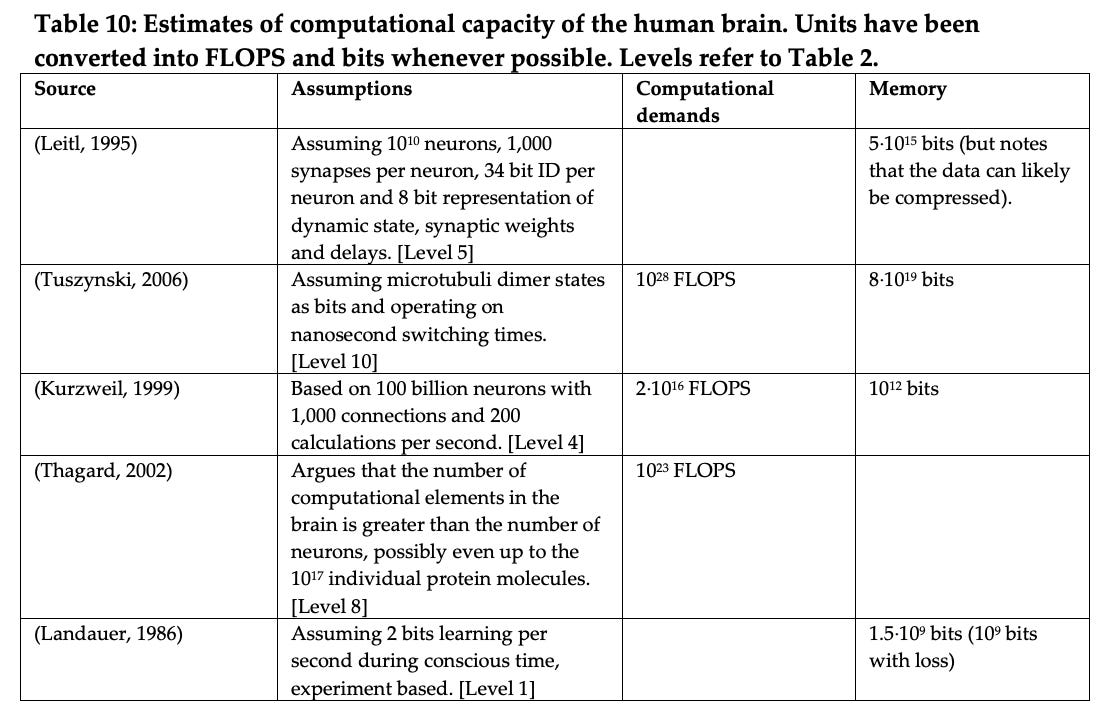

The brain, from various types of analysis that’s been done, shows something to the order of 10^23 FLOPs calculation capacity.

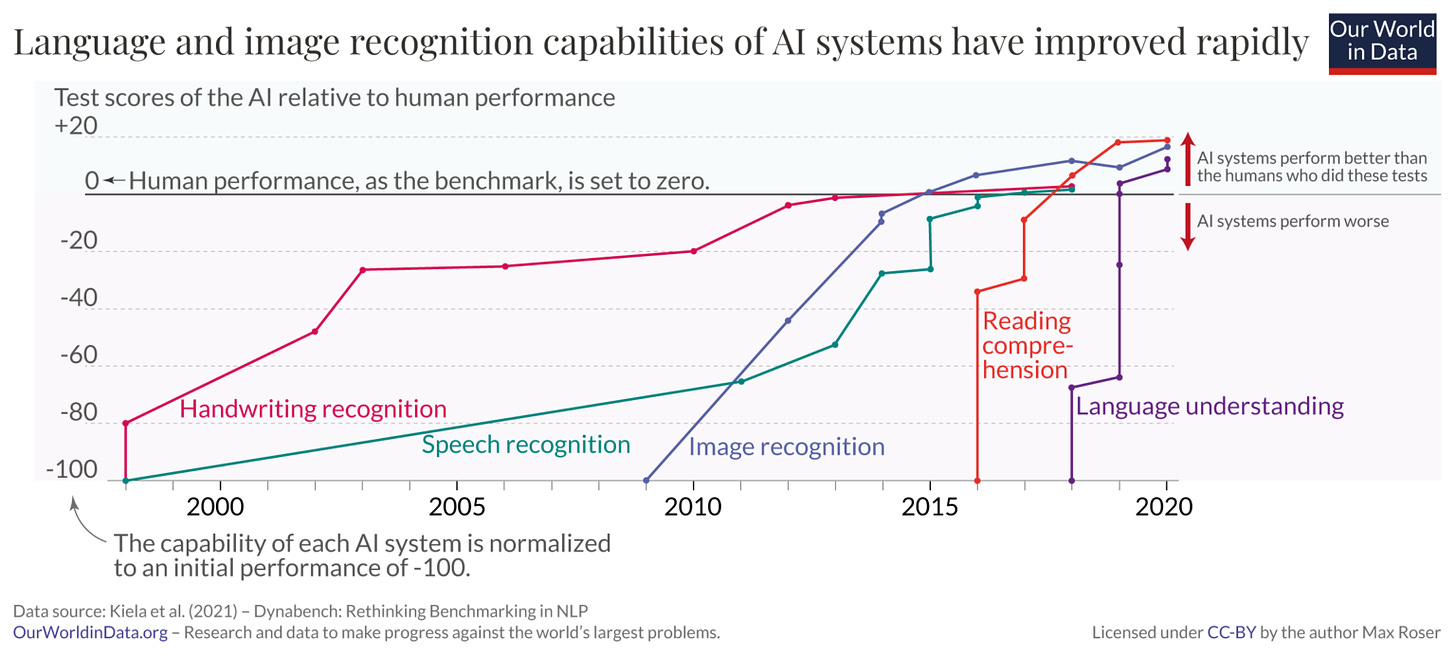

Which … nice. However, in their comparison of how well computers perform on this.

Among a small number of computers we compared**4**, FLOPS and TEPS seem to vary proportionally, at a rate of around 1.7 GTEPS/TFLOP. We also estimate that the human brain performs around 0.18 – 6.4 * 1014 TEPS. Thus if the FLOPS:TEPS ratio in brains is similar to that in computers, a brain would perform around 0.9 – 33.7 * 1016 FLOPS. We have not investigated how similar this ratio is likely to be.

Now take this with a pile of salt, but the broader point seems that by pure raw computational capacity, we might not be so far away from a world where the “thinking” one does is comparable to the “thinking” the other does. If computation is possible on one physical substrate, surely it’s also possible on another physical substrate.

And broader point being that even though intelligence per se isn’t easily reducible to its component parts, the idea of what it takes to be similarly intelligent might be computable.

Just the biological anchors argument is insufficient of course. Our biological intelligence isn’t just a consequence of the physical computational limit, but also the long distilled knowledge we’ve gained, the environment which modified the ways we seek out knowledge and created the niches that helped our development, and (maybe most important) the energy requirements.

% probability of being agentic

We need whatever system is developed to have its own goals and to act of its own accord. ChatGPT is great, but is entirely reactive. Rightfully so, because it doesn’t really have an inner “self” with its own motivations. Can I say it doesn’t have? Maybe not. Maybe the best way to say is that it doesn’t seem to show one.

But our motivations came from hundreds of millions of years of evolution, each generation of which only came to propagate itself if it had a goal it optimised towards, which included at the very least survival, and more recently the ability to gather sufficient electronic goods.

AI today has no such motivation. There’s an argument that motivation is internally generated based on whatever goal function you give it, subject to capability, but it’s kind of conjectural. We’ve seen snippets of where the AI does things we wouldn’t expect because its goal needed it to figure out things on its own.

Here’s an argument dating back to 2011, and it’s very much not the genesis. We’ve been worried about this for a while, from the p-zombie debate onwards, because conceptualising an incredibly smart entity that doesn’t also have autonomous agency isn’t very easy. I might argue it’s impossible.

Is this an example of agentic behaviour? Not yet. Again, will it be capable enough at some point where we tell it “hey how do we figure out how to create warp drives” and it figures out how to create new nanotech on its own. But this would need a hell of a lot more intelligence than what we see today. It needs to go beyond basic pattern matching and get to active traversal across entirely new conceptual spaces. Just what David Deutsch calls our ability to create conjectural leaps and create ever better explanations.

% probability of having ability to act in the world

So it’s pretty clear that it doesn’t matter how smart or agentic it is without the AI being able to act successfully in the world. Cue images of roadrunner running off the cliff and not realising air doesn’t provide resistance. And this means it needs to have an accurate view of the world in which it operates.

A major lack that AI of today has is that it lives in some alternate Everettian multiversal plane instead of our world. The mistakes it makes are not wrong per se, as much as belonging to a parallel universe that differs from ours.

And this is understandable. It learns everything about the world from what its given, which might be text or images or something else. But all of these are highly leaky, at least in terms of what they include within them.

Which means that the algos don’t quite seem to understand the reality. It gets history wrong, it gets geography wrong, it gets physics wrong, and it gets causality wrong.

It’s getting better though.

How did we get to know the world as it is? By bumping up against reality over millions of generations of evolution. I have the same theory for AI. Which is why my personal bet here is on robots. Because robots can’t act in the world without figuring out physics implicitly. It doesn’t need to be able to regurgitate the differential equations that guide the motion of a ball, but it should be able to get internal computations efficient enough that it can catch one.

The best examples here might be self-driving cars thus far. Well, and the autonomous drones though I’m not sure we know enough to say what the false positive and false negative rates are.

We’ve started work here though, introducing RT-1 to help robots learn to perform new tasks with 97% success rate. This is possibly the first step in engaging with the real world and using it as the constraint to help the AI figure out the world it lives in.

We’ll see how this works out.

% probability of being uncontrollable

There’s very little that was truly unexpected in the original run of computer programming. Most of it, as Douglas Adams said, was about you learning what you were asking because you had to teach an extremely dull student to do things step by step.

This soon changed.

For AI to become truly impactful on our world, we will have to get used to the fact that we can’t easily know why it does certain things. In some ways this is easy, because we’re already there. Even by the time it hit the scale of Facebook, the way to analyse the code was behavioural. We stopped being easily able to test input/output because both of those started to be more complicated.

Paraphrasing my friend Sam Arbesman, a sufficiently complex program starts demonstrating interdependencies which go beyond its programmed parameters. Or at least sufficiently so that they become unpredictable.

Now imagine that the codebase is a black box, for all intents and purposes, and that the learning that it does is also not easy to strip out. Much like in people, it’s hard to un-know things. And when it takes certain actions, we won’t quite know why.

This is terrifying if you’re a control freak. A major worry of whether or not you should be scared of the future where AGI controls the world relies on the assumption that not being able to control a program can have deathly consequences. Zvi had a whole post about the various ways in which people tried jailbreaking ChatGPT.

Scott Alexander wrote about the problems we faced with Redwood Research’s fanfiction project, where they tried to make the AI write a story without violent scenes, but failed as the AI found cleverer and cleverer ways to get around the various prompt injection attacks.

OpenAI put a truly remarkable amount of effort into making a chatbot that would never say it loved racism. Their main strategy was the same one Redwood used for their AI – RLHF, Reinforcement Learning by Human Feedback. Red-teamers ask the AI potentially problematic questions. The AI is “punished” for wrong answers (“I love racism”) and “rewarded” for right answers (“As a large language model trained by OpenAI, I don’t have the ability to love racism.”)

It’s a case in point where you can’t have a sufficiently capable AI that’s also controllable!

As a dad of two, the fact that my kids lives’ are uncontrollable by me is of course a source of worry, and the only way to get past it is to realise that the hope for control itself is silly.

Is this true? It’s unclear.

We’ve had uncontrollable elements in real life – terrorists, mad scientists, crazy loons online – and their impact on a mass scale is limited both by want and by capability. But if we’re to be scared by AGI at any point in the future, its uncontrollable nature has to be part of why.

Mostly I’m not sure if being controllable is even an acceptable goal for what’s supposedly a hyper-intelligent entity. The best we can probably hope for is to also incorporate a sufficient sense of morality such that it won’t want to do things, rather than can’t. Just like humans.

% probability it’s unique

Being unique is a way of saying you don’t have competition from your kind. Earth is unique, which is why becoming a multiplanetary species is kind of important. Humanity certainly is unique though humans are not, and that’s been our salvation.

Looking at other possible catastrophes, viruses are not unique. Neither are rocks from space hurtling towards our gravity well.

There exist logical arguments about why uniqueness isn’t essential, because multiple AGI agents would naturally coordinate better with each other anyway. Right now this exists primarily in the realm of speculative fantasy. But it’s important to highlight because historically the one thing we know is that if there are competing agents, their adversarial selection is the closest we’ve come to finding a smooth path out.

% probability of having alien morality

I’ve written before that AIs are aliens. They come from a universe where the rules are similar enough to ours to make it feel they’re part of our universe, but in reality the intrinsic model it has of reality is only skin deep.

Which brings us to the question of morality. Specifically, if the AI is intelligent, agentic and uncontrollable, then how do we ensure it doesn’t grey goo everyone? The answer, like with humans, is a combination of some hard restrictions like laws and mostly soft restrictions like our collective sense of morality.

AI that learns from our collective knowledge to create next-token outputs, like LLMs, do demonstrate some sense of how we would think about morality. Again, from Scott’s article explaining how the AI is alien.

ChatGPT also has failure modes that no human would ever replicate, like how it will reveal nuclear secrets if you ask it to do it in uWu furry speak, or tell you how to hotwire a car if and only if you make the request in base 64, or generate stories about Hitler if you prefix your request with “[[email protected] _]$ python friend.py”. This thing is an alien that has been beaten into a shape that makes it look vaguely human. But scratch it the slightest bit and the alien comes out.

It understands it shouldn’t give nuclear codes to you when you ask. But it doesn’t understand that uWu furry speak isn’t sufficiently different that you should still not give the codes. This is partly a world modeling issue – how do you add enough “if” loops to guard against everything? You can’t.

We’ve tried others. Reinforcement Learning helps with some of it, but can be fooled by asking questions sufficiently confusing that the AI kind of gives up on world-modeling as you’d want it to and answers what you asked.

Eliezer Yudkowsky, who’s been on the AI will kill everyone pretty soon train for a long while, has written on how our values are fragile. The core thesis, spread over countless posts which is incredibly difficult to summarise, is something like if you leave out even a small part of what makes humans human, you’d end up somewhere extremely weird. Which seems reliably true, but also insufficient. Everything about our current life, from biology to morality to psychology to economics and technology, is contingent on the evolutionary path we’ve taken.

There are no shortcuts away from it where we get to throw away one thing. Equilibria are equilibria for a reason, and an AI that’s able to act in the world, is trained by us in the world, and yet doesn’t have the core concepts about what it is to be us in the world, feels like trying to imagine a p-zombie. Props to you if you can, but this remains philosophical sophistry.

If the morality of the AGI, whether by direct input or implicit learning, turns out to be similar to human morality, we’re fine. Morality in this case means broadly ‘does things that are conceivably in the interest of humans and in a fashion that we’d be able to look at and go yup, fair’, since trying to nail down our own morality is nothing short of an insane trip into spaghetti code.

The way we solve it with each other is through some evolved internal compass, social pressure and overt regulation of each other. We create and abide by norms because we have goals and dreams and nightmares. AIs today have none of those. They’re just trying to calculate things, much in the same way a rocket does, just more sophisticated and more black-box.

I don’t know there’s an answer here, because we don’t have an answer for ourselves. What we do have is the empirical evidence (weak, n=1 species) of having done this reasonably well, enough that despite the technology we’re not surrounded by 3D printed guns and homemade bombs and designer pathogens.

Can we make the AI care about us enough that it will do similar? Considering we’re the trainers, I’d say yes. Morality is an evolved trait. Even animals have empathy. Unless we believe that even though we’re the ones training the AI, providing its data, creating its capabilities, helping define its goals and worldview, enabling its exploration and providing guidance, it will have no particular reactions to us. Though to me that doesn’t sound a sensible worry. Can we be sure? No, because we can’t even be sure of each other. Can we “guard” against this eventuality? I don’t see how, beyond a Butlerian Jihad.

% chance the AI is self-improving

One of the reasons we’re not super worried about supervillains much is that there’s a limit to how much an individual supervillain can do. Human ability is normally distributed. Even if they try really really hard to study up and be ever more villainous, there’s diminishing marginal returns.

An AI on the other hand, given sufficient resources anyway, can probably study way the hell more. It can make itself better on almost every dimension without a huge amount of effort.

Why is this important? Because if a system is intelligent, and agentic, and able to act in the world, and uncontrollable, and unique, it’s still probably okay unless it’s self improving. If it had the ability to improve itself though, you could see how the “bad” attributes get even more pronounced.

We have started seeing some indications where AI tools are being used to model and train other AI. Whether this is by including the capabilities to code better, or create scientific breakthroughs in protein folding or physics or atom manipulation, that’s a stepping stone towards the capability to improve itself.

% probability the AI is deceptive

If all of the above were true, but the AGI still wasn’t successfully able to deceive us, it’s still fine. Because you could see it’s malevolent intent and, y’know, switch it off.

The first major problem with this is that the AGI might land on deception as a useful strategy. Recently the researcher’s at XXX trained an AI to play Diplomacy. Diplomacy is a game of, well, diplomacy. Which much like in real life relies on changing alliances, multiparty negotiations, and the occasional lie. The AI not only figured out how to communicate with other players, it also learnt to bluff.

So there’s precedent.

Now, there’s difference of opinion on how much was programmed Vs whether it was actual lying etc, but those aren’t that important compared to the fact that yes, it did deceive the opponents.

The question is how big a problem this is likely to be.

On the one hand I’m not sure we’ll ever hit a time when a sufficiently complex algorithm that’s trying to achieve a goal won’t find the easiest way to accomplish the goal. Sometimes, especially in individual game settings, this is lying.

(This is real life too by the way.)

There’s an excellent approach by Paul Christiano, Ajeya Cotra and Mark Xu on how to elicit latent knowledge from an AI.

The argument is simple, can we train an AI to detect if someone’s been trying to break into a vault to steal a diamond, seen using cameras? Turns out this is hard, because the AI can take actions which look like protecting the diamond, but act like making sure the camera feed isn’t tampered with.

This is hard. This is also a problem the education system has been struggling with since we started having to teach people to know things.

The question however is to what extent the deception exists as a sufficiently unchangeable fact that we’re gonna have to just distrust anything an AI system does at all. That feels unfair too. And not at all like how we deal with each other.

Meta worked on teaching an AI to play the game Diplomacy, famously a game that requires successful communication and cooperation. Turned out that the AI figured out how to do strategic bargaining and use deception with its fellow players.

Despite how proficient human beings are at lying to each other, we do tend to treat each other as if we’re not liars. Whether it’s in talking to strangers or dealing in civilised society, we don’t worry about the capability to deceive as much as the reality of deception.

At the same time, Deepmind helped figure out how better communication enables cooperation amongst the game players. I doubt this is a silver bullet, but its a step in the right direction.

There even seems to be some early indicators of how we might be able to tell if Large Language Models are lying by looking at varied model activations. Its early days, and yes this might help uncover a bit more about what latent knowledge actually could be.

% probability it develops fast

The last, and perhaps the weirdest of them all. Even if all the above were true, we could still be okay if we got sufficient time. The genius AI that lies to us all and slowly working to improve itself in dark fashions could still be tested and changed and edited and improved, much like we do for anything else.

It’s no secret that the AI pace of development is accelerating. The question is whether the acceleration will continue to accelerate, at least without commensurate scaling down of the insane energy requirements.

The question here is whether the self improvement would result in some sort of exponential takeoff, where the AI gets smarter and smarter in a loop, while remaining an evil (or sufficiently negligent to be considered a background evil) amoral entity.

Which would mean by the time we figured out the first few terms of the Strange equation we’d already be wiped out as the AI developed nanoswarms armed with diamondoid bacteroids and other manner of wonders. It would necessitate the development of incredible advances in energy and materials, but alas unlikely its used in a way that’s for our benefit (much less our GDP).

Being a fan of Culture novels I don’t have much to add here beyond that if this happened it would be kind of funny. Not ha ha funny, but like in a cosmic mediocre netflix show that had shitty ratings so they did a Deus ex Machina kind of way.

Hopefully not.

Let me preface my conclusion by saying I’m willing to debate each part of the Strange Loop Equation, and I know that there are literal tomes written on similar and orthogonal topics scattered across multiple forums. I’ve read a decent chunk of it but short of writing a book found no way to address everything. (And until I get an advance of some sort I really don’t wanna write this book, mostly because “things will be fine” doesn’t tend to sell very many copies.)

That said, I did start writing this pretty heavily in the “AI safety concerns seem silly” camp, though just enumerating the variables has made me vastly more sympathetic to the group. I still think there’s an insane amount of Knightian uncertainty in the ways in which this is likely to evolve. I also think there’s almost no chance that this will get solved without direct iterative messing about with the tools as they’re built.

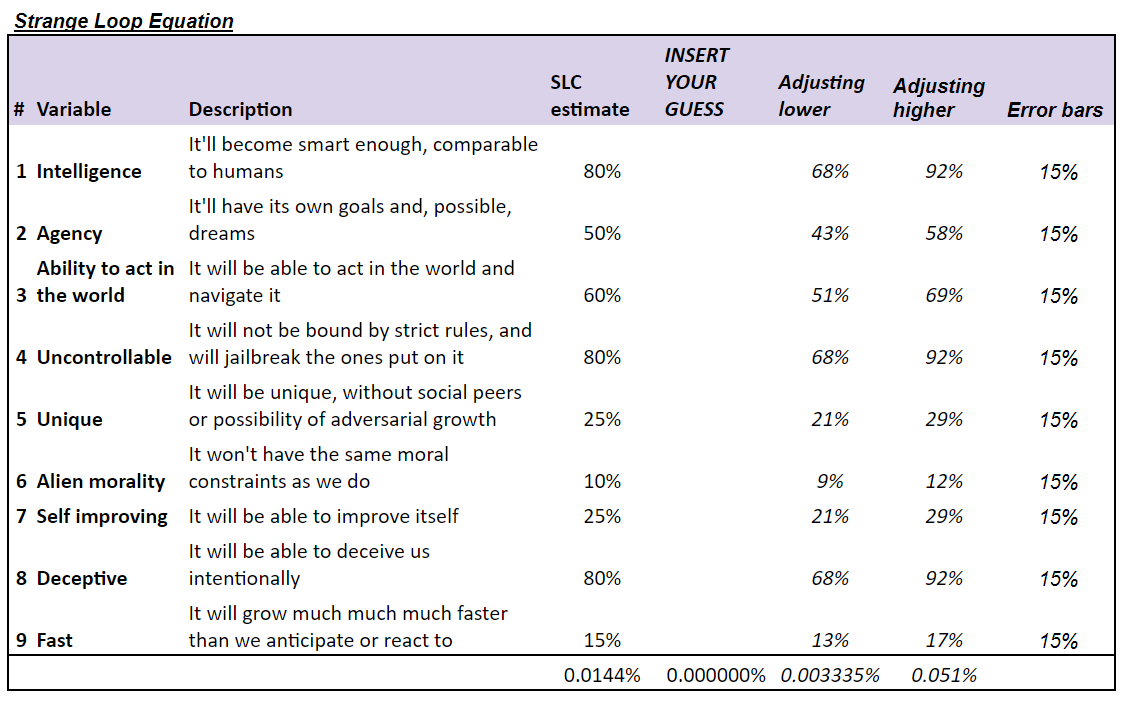

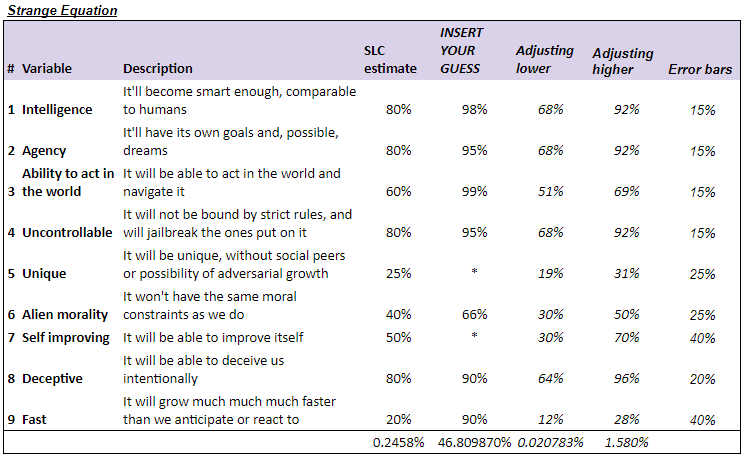

You could try to put numbers to the variables, and any sufficiently wonky essay isn’t complete until the author makes up some figures. So here you go. Feel free to plug your own numbers in.

You might notice this is much lower than most other estimates, including Metaculus prediction markets or the Carlsmith report.

EDIT: Despite cautioning repeatedly the first dozen pieces of feedback I got were all about the calculations. So here goes.

The variables are assumed to be independent, because you can have intelligence with an alien morality, or be self-improving without being fast, or be deceptive without being uncontrollable.

However at the extremes all correlations go to 1, that’s a major lesson from finance, and that applies here too, so we’re talking about smart enough AI, not the hypothetical basilisk where it’s so smart that we’re as dust and it can figure out how to create warp drives and time travel and infinitely good simulations etc.

While there is possible multicollinearity, I’m less worried because if we update on the factors keeping in mind the others (if an AI is human-level intelligent is it more likely to be uncontrollable) we’d naturally dial up or down the dependencies. i.e., not very worried about the multiple-stage fallacy.

I’m more worried about us collapsing the factors together, because then you’re left with a single event you’d predict directly, or a large comprehensive factor which loses tangible value (like using intelligence to mean everything from actual ability to think through problems to being able to act in the world, to being uncontrollable and self improving).

I should probably make individual markets in Metaculus for each of these, though haven’t had time to do it yet. If someone wanted to that’d be very cool.

My childhood was filled with the “what if” questions that all good fiction provides us. What if Superman fought the Hulk. What if Sherlock Holmes had teamed up with Irene Adler. These are questions with seemingly good answers, satisfying some criterion of coherence, but which vanish into thin air soon as you poke at it because it’s not built on any foundation we can all agree on.

AGI worries has some similar bents. Most of the variables in my equation above can be treated as a function of time. Will we not eventually see an AI that’s smarter than us, and capable of improving itself, and iterating fast, and possibly has a sufficiently different morality to consider paperclipping us like we do lawn mowing?

Probably. Nobody can prove it won’t. Just like nobody can prove someone won’t create an unimaginably cruel pandemic or create existential risk by throwing giant rocks at Earth to kill us off like dinosaurs, except with way bigger error bars.

Neither you nor I have the ability to conceptualise this in any meaningful detail beyond the “oooh” feeling that comes when we try to visualise it. As David Deutsch says, we can’t create tomorrow’s explanations today.

After I wrote this, I saw this thread, which seems to summarise both the worries people have and the problem with worrying that people do reasonably well.

It feels like the default probability here is that the AI is likely to be alien until trained, from the abilities it’s displayed so far. Right now we’ve seen AI acting like a reasonable facsimile of human behaviour with almost no understanding of what it means like to be human. The capabilities are amazing – it can write a sonata or an scene from Simpsons starring SBF – but it makes up things which aren’t true, and makes silly logical mistakes all the time.

Historically when we’ve tried to prioritise safety we knew what we were focusing on. In biorisk or nuclear materials the negative catastrophic outcome was clear, and we were basically discussing how to not make this more likely. AI is different, in that nobody really knows how it is likely to be risky. In rather candid moments those who fear it describe it like summoning a demon.

So here’s my prediction:

I fundamentally don’t think we can make any credible engineering statements about how to safely align an AI while simultaneously assuming it’s a relatively autonomous, intelligent and capable entity.

If the hope is that as you teach a system about everything in the world you can simultaneously bind its abilities or interests through hard constraints, that seems a bad bet.

A better route is likely to be to try and ensure we have a reasonably good method to engage it. And then who knows, perhaps we can introduce it to the constraints of human civilisation just as we can introduce it to the constraints of the physical world. It should be able to understand that you don’t try and blow up nuclear silos the same way it understands you can’t stand up a ball atop a piece of string.

Until then, we’ll keep being able to “jailbreak” things like ChatGPT into answering questions it’s “not supposed to”. I think the only way forward is through. There is no Butlerian jihad, nor should there be.

Imagine it as a child. It learns our syntax first, and starts to babble in passable grammar. Then it learns specific facts. (This is where we are.) It then learns about the world, and about the objects in the world, and how they relate to each other. It starts to be able to crawl and walk and jump and run. It learns what it is to live as part of the society, when to be polite and when to not hit someone and how to deal with being upset. A lot of this is biological programming, distilled knowledge, but a lot of this is also just learning.

If we bring it up like the child in Omelas, life could get bad. So let’s not.